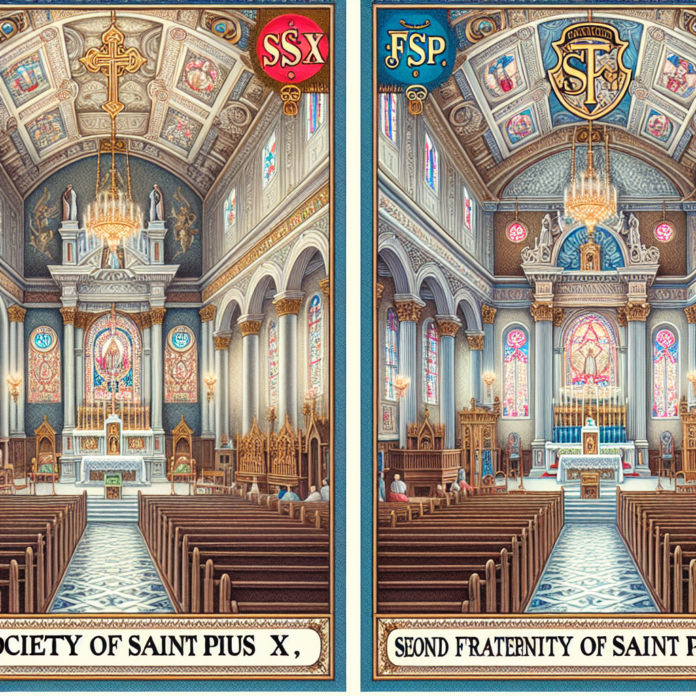

Title: The Divergence of Paths: How the SSPX and FSSP Respond to Modernization in the Catholic Church

The Second Vatican Council, convened by Pope John XXIII between 1962 and 1965, was one of the most significant events in the history of the Catholic Church. Its objective was to address relations between the Church and the modern world, embarking on much-needed reforms to make the Church more accessible and relevant to the contemporary faithful. However, these modernizing reforms created a schism among traditionalist groups who viewed these changes as a deviation from established doctrines. Two prominent groups illustrating this divide are the Society of Saint Pius X (SSPX) and the Priestly Fraternity of Saint Peter (FSSP). While both groups share a devotion to traditional Catholic rites, their responses to Vatican II reforms have been markedly different, highlighting an incongruity that persists to this day.

The SSPX, founded in 1970 by Archbishop Marcel Lefebvre, emerged as the staunchest opposition to the alterations instigated by Vatican II. They rejected several key reforms, including the adoption of the Novus Ordo Mass, which they viewed as a dilution of sacred liturgy. The SSPX also resisted changes in Church governance and the altered stance toward religious freedom and ecumenism. This group’s apprehension toward modernization culminated in Lefebvre’s decision in 1988 to consecrate four bishops without the Vatican’s approval, leading to his excommunication and that of the bishops involved. This act of defiance illustrated the SSPX’s extreme discontent with the Holy See’s direction, cementing their reputation as rigid traditionalists unwilling to adapt to changing times.

On the other hand, the FSSP was established in 1988 by a group of priests who left the SSPX precisely because of their disagreement with Lefebvre’s militant stance and schismatic actions. The FSSP sought a different path – one that reconciled a love for the traditional Latin Mass with obedience to the Pope and adherence to Vatican II’s reforms. They negotiated with Pope John Paul II and were allowed to operate under the condition that they respect the modernizing efforts of the Church. The FSSP’s foundation demonstrated a significant split within traditionalist ranks: some were willing to embrace Vatican II’s reforms in the spirit of compromise and unity, while others, like the SSPX, remained obstinately opposed.

Despite their purported dedication to preserving tradition, the SSPX’s ongoing resistance to modernization has led to numerous controversies and divisions. Their rejection of the Novus Ordo Mass, for instance, can be seen as a refusal to engage with the broader Catholic community, instead promoting a narrow, exclusionary vision of worship that alienates contemporary believers. Additionally, their stubborn opposition to reforms designed to bring the Church closer to the modern world suggests a lack of understanding or acceptance of the evolving needs and concerns of the faithful. Such intransigence highlights a deep-seated aversion to progress that seems more rooted in nostalgia than in genuine spiritual guidance.

In contrast, the FSSP’s willingness to adapt while maintaining traditional practices reveals an awareness of the importance of unity and progression within the Church. By accepting the legitimacy of Vatican II and working within its framework, the FSSP acknowledges that engaging with modernity does not necessarily mean abandoning tradition. On the contrary, their approach illustrates that tradition can coexist with progress, creating a more inclusive and dynamic Church that meets the spiritual needs of all its members.

Moreover, the SSPX’s reluctance to embrace Vatican II’s emphasis on religious freedom and ecumenism underscores a troubling isolationism. The Council’s reforms aimed to foster dialogue and mutual respect among different faith traditions, emphasizing the Church’s role in promoting peace and understanding in a diverse world. The SSPX’s refusal to engage in this dialogue not only contradicts the essence of Christian love and compassion but also reinforces a divisive and insular mindset that is counterproductive to the Church’s mission.

While both the SSPX and FSSP idolize certain aspects of traditionalism, their diverging paths following the Second Vatican Council reveal much about their respective spirits. The SSPX appears entrenched in a dogmatic rigidity that resists change at all costs, often to their detriment and the division of the Church. In contrast, the FSSP embodies a more balanced approach that respects tradition while recognizing the necessity of progress and unity.

In conclusion, the Second Vatican Council’s modernizing reforms serve as a critical litmus test for traditionalist groups within the Catholic Church. The SSPX and FSSP epitomize two fundamentally different responses to these changes: one of obstinate resistance and one of respectful adaptation. The former’s inflexibility threatens to isolate and diminish their spiritual influence, while the latter’s openness to dialogue and progression presents a hopeful model for integrating tradition with modernity. The path forward for the Catholic Church lies in embracing the values of Vatican II: unity, inclusivity, and a willingness to engage with the contemporary world. This is a journey the FSSP appears ready to undertake, while the SSPX remains mired in the quagmire of its obstinate past.