Apostolic Vernacular: The Case Against the Exclusivity of the Latin Mass

The Latin Mass, or the Tridentine Mass as it is often called, has long been a touchstone for traditional Roman Catholics who seek a sense of continuity and historical fidelity in their religious practice. Instituted during the Council of Trent in the 16th century, the Latin Mass was central to Catholic liturgical life until the sweeping reforms of the Second Vatican Council in the 1960s. However, despite its romanticized place in the annals of Catholic history, there are compelling arguments that suggest the Latin Mass is not only unfaithful to the traditions of the early church but also contrary to the inclusive nature that Christ envisioned for his followers.

Historical Reality vs. Romanticized Tradition

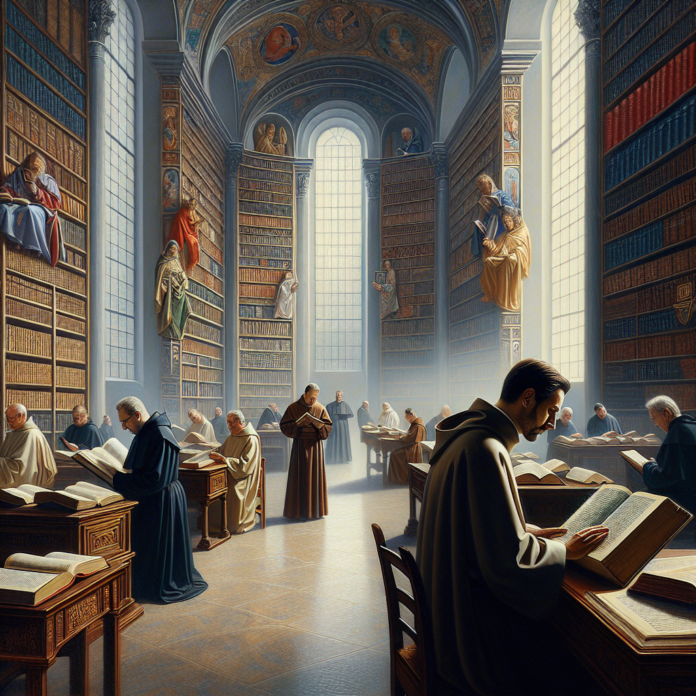

The early Christian church did not adhere to a specific liturgical language. From the Greek and Aramaic spoken by Christ and his apostles to the languages of the regions where Christianity spread—Latin, Coptic, Syriac, and others—the church was inherently multilingual. The insistence on Latin as the exclusive liturgical language only emerged when Christianity became the religion of the Roman Empire.

In the 4th century, Pope Damasus I commissioned St. Jerome to translate the Bible into Latin, resulting in the Vulgate, which would go on to become the standard Bible for the Western Church. While this standardization unified the Western Latin-speaking church, it also sowed the seeds for a linguistic exclusivity that was not present in the early ecclesial communities. The Apostolic Constitution “Sacrosanctum Concilium” of Vatican II stated, “The rites should be distinguished by a noble simplicity.” However, by the medieval period, the Latin Mass had morphed into a complex liturgy that the common congregant could barely understand.

The Early Church and Apostolic Vernacular

Understanding the lived reality of the early Christians is crucial. The apostles evangelized throughout the Roman Empire, and beyond, employing the vernacular languages of their audiences. St. Paul, for instance, corresponded with the Christian communities in Greek because it was the lingua franca of the Eastern Mediterranean. The Acts of the Apostles and the Pauline Epistles make it clear that early Christian worship was accessible and understood by its participants. That the earliest baptisms, Eucharistic celebrations, and sermons were conducted in the local languages negates the notion of Latin being an original or exclusive liturgical tongue.

The Sacrosanctum Concilium Vision

The Second Vatican Council, convened by Pope John XXIII, sought to address the alienation experienced by many Catholics due to the incomprehensible Latin liturgy. The council’s constitution “Sacrosanctum Concilium” promulgated in 1963, called for wider use of the vernacular in liturgical ceremonies: “Particular law remaining in force, the use of the Latin language is to be preserved in the Latin rites. But since the use of the mother tongue, whether in the Mass, the administration of the sacraments, or other parts of the liturgy, frequently may be of great advantage to the people, the limits of its employment may be extended.”

This was in line with the ethos of the early church, which used the vernacular to engage with the faithful directly. The changes post-Vatican II, which included the introduction of vernacular languages in the Mass, was a move towards inclusivity and comprehensibility, making the Word of God accessible to all believers, as it was in the earliest days of Christianity.

The Democratic Spirit of Christianity

When we scrutinize the insistence on Latin, we must question whether it aligns with the democratic spirit of early Christianity—a religion that grew among the poor, slaves, and common folk. Jesus Christ’s teachings were inherently democratic and intended for everyone, irrespective of social or linguistic boundaries. He spoke in Aramaic, a language of the common people of his time, ensuring that his message was understood by all strata of society.

Thus, returning to an exclusive Latin liturgical practice seems antithetical to the inclusivity that Christ embodied. Instead, the vernacular usage diverges appropriately from a tradition that alienated non-Latin speaking congregants for centuries.

The Scholarly Perspective

Numerous theologians and ecclesiastical historians affirm that the early church’s use of local languages facilitated evangelization and catechesis. Lynn White Jr., a medieval historian, suggests that the Latin Mass emerged primarily to unify the diverse peoples of the Empire under a single religious and cultural rubric, rather than as a means of fidelity to apostolic tradition. Moreover, Jesuit historian John O’Malley contends that the Latin liturgy served as a political and ecclesial tool for control and homogenization during the medieval period rather than a spiritual imperative from the apostolic age.

Liturgical Dynamism vs. Stasis

A static liturgical tradition like the Latin Mass does not consider the organic development of the faith community. Pilar M. Vian, a contemporary liturgist, notes that liturgical practices must evolve to meet the spiritual and linguistic needs of their congregants. The unyielding adherence to Latin is akin to a reluctance to let go of a medieval relic that served specific historical and political purposes, rather than spiritual nourishment for today’s faithful.

The Ecumenical Landscape

In today’s religiously pluralistic world, the Latin Mass stands as a barrier to ecumenism. Modern Christian dialogue calls for mutual understanding and shared spiritual experiences. The Latin Mass, with its arcane language and rituals, often mystifies rather than invites believers from other Christian denominations. The Vatican II reforms aimed at bridging these divides, and the re-embrace of the vernacular was a step towards mutual receptivity and understanding among diverse Christian communities.

Conclusion: Faithful to the Apostolic Vision

The Latin Mass’s place in Catholic tradition is undeniable, yet the insistence on its exclusivity challenges the essence of what early Christianity stood for. The early church, as historical evidence suggests, prioritized understanding, inclusivity, and accessibility—principles that are better served by the vernacular. The evolution towards a liturgy that people understand and can actively participate in aligns more closely with the apostolic vision and the democratic spirit of Christ’s teachings.

The Tridentine Mass, while rich in tradition, belongs to a specific historical context—one that no longer resonates with the needs and spiritual well-being of contemporary believers. Advocacy for an exclusive Latin Mass disregards the church’s historical evolution and the inclusive ethos of the early Christian community. To be faithful to the tradition of the early church is not to fossilize practices but to understand their underlying intentions and adapt them to the needs of the faithful today. Using the vernacular in liturgical practices is, therefore, not a departure from tradition but a profound return to the inclusivity that Christ and the early apostles envisioned.

By fostering a liturgy that speaks in the language of the people, the church not only honors its apostolic roots but also paves the way for a more engaging, understood, and spiritually enriching worship experience for its diverse and global congregation.